Community Liaison | Blog

Food Insecurity and Mental Health

Surely, we have all experienced the sensation of being “hangry” and can attest to the fact that we are not our best selves when we’re hungry. Coupling this with the stress of not having enough resources to address one’s experience with hunger and food insecurity, and not know if or when that situation may change, not only impacts one’s physical health, but also increases the risk of developing mental health illnesses.

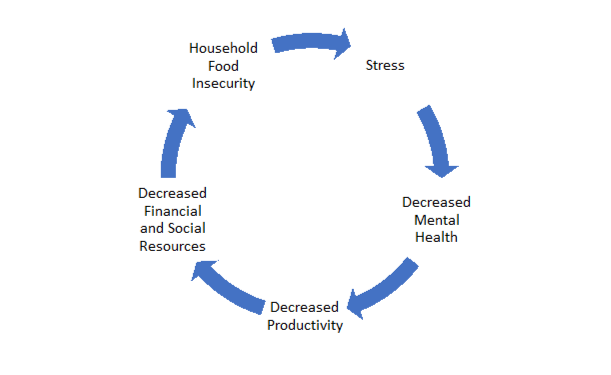

Food insecurity and mental health have a bidirectional circular relationship, where regardless of which comes first, they have considerable influence on each other. For example, the state of food insecurity can cause depression whereas being depressed can also contribute to food insecurity.

Research has demonstrated that the more severe a household’s food insecurity is, the greater their odds are of experiencing adverse mental health outcomes (Fang, Thomsen, and Nayga Jr., 2021; Jessiman-Perreault & McIntyre, 2017; Tarasuk, Cheng, & Kurdyak, 2018). Stress, such as the worry of figuring out where one’s next meal will come from, is one of the many pathways that may lead someone to experience adverse mental health outcomes. Factoring in this stress with genetics, social factors, and individual factors, such as a history of trauma and poor coping skills may exacerbate adverse mental health outcomes.

A 2018 study in Ontario (Tarasuk, Cheng, & Kurdyak, 2018) found that over a 12-month period, 40.4% of people who accessed professional mental health supports were severely food insecure. They had to make extensive compromises, such as reducing food intake to stretch their income (Tarasuk, Li, Fafard St-Germain, 2022). This is compared to 15.6% of food secure individuals.

We’re not our best selves when we’re hungry.

The link between food insecurity and mental health is too strong to ignore. Jessiman-Perreault and McIntyre (2017) cite food insecurity as a public health problem requiring macro-level intervention. They surmise an 8.9%-16.0% decrease in the reporting of six adverse mental health outcomes (depressive thoughts in the past month, major depressive episodes in the past year, anxiety disorder, mood disorders, fair/poor mental health status, suicidal thoughts in the past year) if people experiencing severe food insecurity were to become food secure

The link between food insecurity and mental health is too strong to ignore.

One-third of hospitalizations across Canada are due to mental health (Jessiman-Perreault & McIntyre, 2017). Given the relationship between food insecurity and mental health, and the fact that Alberta has the highest rates of food insecurity across the ten provinces, it is possible that this number is even higher if we look locally. However, more research will need to be done to determine if this is the case.

Hence, sufficient and wholistic interventions that target several domains of health, such as mental, physical, social, and spiritual health, are crucial to decreasing both food insecurity and mental health issues. Food Banks Canada (2021) identifies that quality and affordable mental health support, living wage, affordable housing, and support for those who fall out of the work force (i.e. Strong labour laws, adequate unemployment benefits) will lead to decreased rates of food insecurity, save taxpayer dollars, and foster a thriving community.

At the Calgary Food Bank, we measure the extent to which receiving an Emergency Food Hamper reduces household stress. As a result, we know that once the worry about accessing food has been removed, people can focus on using diverted funds to meet other needs, such as paying for utility bills, car insurance, or new winter gear. Changes to procedures at the Calgary Food Bank, such as our drive-thru model, and online hamper request form work to increase anonymity for people accessing the Calgary Food Bank. As well, upon hamper pickup, we aim to foster a friendly and non-judgmental space, allowing for the overall well-being of people accessing the Calgary Food Bank to be positively affected. While we can shift our policies practices at an organizational level, a greater societal shift that emphasizes community care is required to truly diminish the shame and stigma associated with asking for help.

Policy intervention that supports the wholistic well-being of an individual is key to fostering a thriving community.

References:

1. Jessimean-Perreault, G., McIntyre, L. (2017). The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults. SSM – Population Health. 3. 464-472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.05.013.

2. Tarasuk, V., Cheng, J., Kurdyak, P. (2018). The relation between food insecurity and mental health care service utilization in Ontario. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 63(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717752879

3. Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca/

4. Food Banks Cananda (2021) 2021 Federal Policy Recommendations. https://www.foodbankscanada.ca/FoodBanks/MediaLibrary/research/FBC-Federal-Policy-Recommendations-2021-EN.pdf